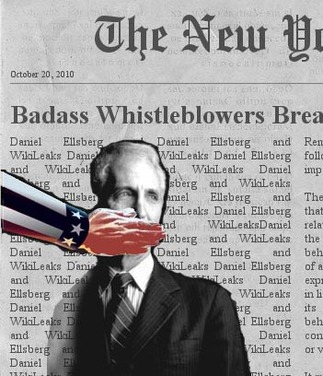

Daniel Ellsberg, the figure that Henry Kissinger proclaimed as “the most dangerous man in America,” paid a visit to Ithaca College on October 20 to discuss his history, his famous copying and distributing of 7,000 classified documents about the Vietnam War in 1971 and its relevance in modern society.

Ellsberg’s visit came at an eerily perfect time; on the eve of WikiLeaks releasing four thousand more documents about the ongoing warfare in Afghanistan, the parallels between Ellsberg’s Pentagon Papers and WikiLeaks’ Afghanistan Dossier is striking. (Read more on WikiLeaks in my classmate Christine Loman's great blog post).Ellsberg said that he supports the efforts of WikiLeaks, and he highlights how essential it is for documents revealing the truth about this war to be released. He said, “We still need the Pentagon Papers of Afghanistan or Iraq. They need to come out now. We don’t have them. But someone does.”

I didn’t realize to what extent the U.S. government tried to silence Ellsberg and half the publication of the Papers. I found it particularly interesting to see, during the screening of The Most Dangerous Man in America, how Ellsberg ultimately disseminated all of the pertinent information. The way that newspapers from across the country tag-teamed the endeavor of publishing these papers was marvelous – when The New York Times was ordered to stop, The Washington Post picked up the story, followed by The Boston Globe and then The Chicago Sun-Times. I couldn’t believe all of the awesome cooperation between the 17 corporate media juggernauts.

WikiLeaks has it a bit easier now to get the word out. In our virtual world, they have the clear advantage over Ellsberg, who had to systematically Xerox all 7,000+ pages. But some of the roadblocks still stand: even if and when these groundbreaking documents are released, we as an American public need to keep the pressure on our government and our media – why have we not yet heard about these stories and these truths? This is the question that we must empower ourselves to ask.

We need to learn from Ellsberg, the “phantom figure” who’s evolved into a hugely important peace activist. He wasn’t afraid of institutional castigation, and we as an American media base shouldn’t be either. In response to Ellsberg’s biting question from 1971—“Wouldn’t you go to prison to help end this war?,”—we should all be able to answer “yes.”

Ellsberg’s visit came at an eerily perfect time; on the eve of WikiLeaks releasing four thousand more documents about the ongoing warfare in Afghanistan, the parallels between Ellsberg’s Pentagon Papers and WikiLeaks’ Afghanistan Dossier is striking. (Read more on WikiLeaks in my classmate Christine Loman's great blog post).Ellsberg said that he supports the efforts of WikiLeaks, and he highlights how essential it is for documents revealing the truth about this war to be released. He said, “We still need the Pentagon Papers of Afghanistan or Iraq. They need to come out now. We don’t have them. But someone does.”

I didn’t realize to what extent the U.S. government tried to silence Ellsberg and half the publication of the Papers. I found it particularly interesting to see, during the screening of The Most Dangerous Man in America, how Ellsberg ultimately disseminated all of the pertinent information. The way that newspapers from across the country tag-teamed the endeavor of publishing these papers was marvelous – when The New York Times was ordered to stop, The Washington Post picked up the story, followed by The Boston Globe and then The Chicago Sun-Times. I couldn’t believe all of the awesome cooperation between the 17 corporate media juggernauts.

WikiLeaks has it a bit easier now to get the word out. In our virtual world, they have the clear advantage over Ellsberg, who had to systematically Xerox all 7,000+ pages. But some of the roadblocks still stand: even if and when these groundbreaking documents are released, we as an American public need to keep the pressure on our government and our media – why have we not yet heard about these stories and these truths? This is the question that we must empower ourselves to ask.

We need to learn from Ellsberg, the “phantom figure” who’s evolved into a hugely important peace activist. He wasn’t afraid of institutional castigation, and we as an American media base shouldn’t be either. In response to Ellsberg’s biting question from 1971—“Wouldn’t you go to prison to help end this war?,”—we should all be able to answer “yes.”